It was a foggy morning. When we were walking to breakfast at 7 AM, it was still dark. You could barely see the other side of the hotel and as we walked I hoped that the ominous weather now was not a reflection of the rest of the day. As we drove down the highway towards La Copa Ranch to meet Ray and Don, the van was silent while we all woke up and adjusted to the dim morning. Part sleepiness part preparation for the day ahead, the music playing softly and the sound of the air conditioning filled the silence.

Day 2 of our mission would start about an hour and a half from La Copa, the ranch where Don and Ray are staying, and where we split between two trucks. The journey was less highway and more small caliche (sediment that hardens when dry and is semi-moldable when wet) roads that have been worn and traveled. It was a bumpy ride to our destination, as it was the day before and likely will be tomorrow. Because I rode with Don yesterday, I rode with Ray today and on our way, more stories and insight were shared. We had been on the road for an hour when we veered into the brush on what first did not look like a road. A short while later, a renewed carved two track path behind us, we reached our starting point.

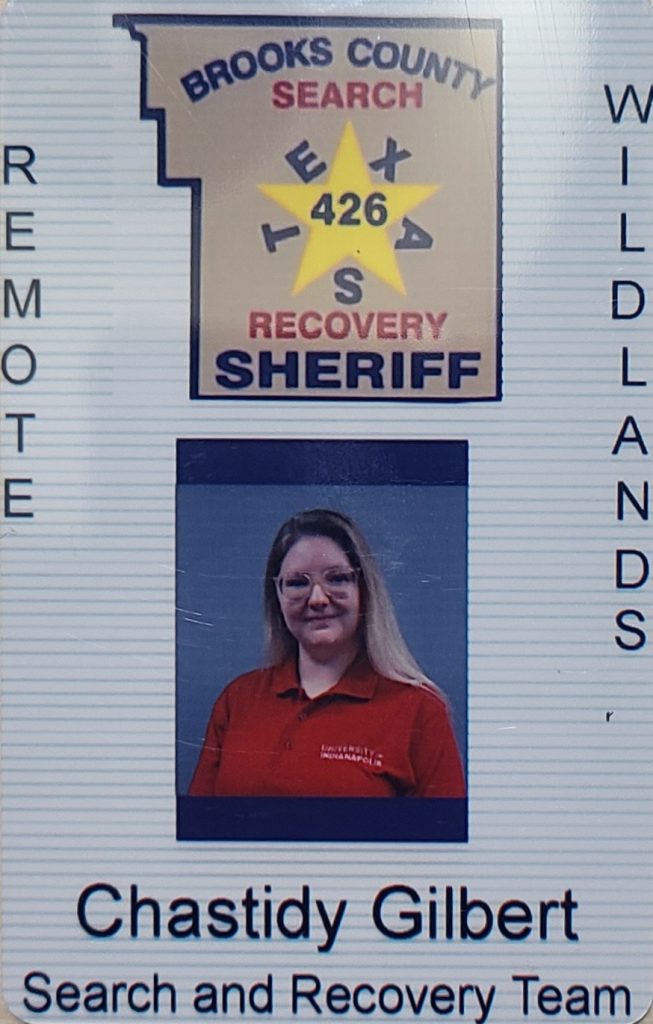

The fog was still in full force when we stepped out of the trucks, with dew drops making the many spiderwebs in the brush stand out. Don began to explain that we were here because of a call that had been made about an individual who had went missing two years prior. There was also the possibility that another individual went missing in this area. They were supposedly at or around the coordinates Don was given (which led to a mot that was searched and cleared previously), and our goal was to fan out and search beyond the coodinates to potentially locate this individual.

We began with line searches of the clearing we parked in and headed due North, sometimes scattering around and peaking into mots. In the beginning, we were not seeing any evidence of human activity, which could include trash or clothes, and it seemed that the day would have a similar result to Day 1. There were quail hunters on the property and every now and then, we would hear voices and gunshots. While we didn’t know a lot about quail hunting (the guns are short range) at the time, this was enough to make us nervous. As we neared the end of the search area, Don suggested we reach the tree line, peak in, and then turn around to line search the opposite side of the clearing on our way back to the trucks. By that time, the sun was starting to peak through and our pants were starting to dry from hiking through wet brush. Don had ventured a little further into the tree line, just where we couldn’t see him, and suddenly our walkies beeped and his voice rang out “ya’ll want to come look at this”. We headed in his direction, and after a few minutes of walking, there were Don and Ray smiling at us, knowing that we would soon be able to jump into the roles we traveled here to do and give this person’s family some long awaited answers.

Our goal for Day 2 was realized, as our search resulted in a recovery. We cannot say for certain whether or not the recovery that was made was related to the call that Don had received, but based on the area and the time line of the related material artifacts found, he will be able to give as much detail as possible in his report to help with potential identification. We searched the surrounding area as thoroughly as possible.

By the peak of our process, the sun was out and bright, so staying hydrated was at the forefront of our minds. We had a 15 minute timer to remind us to drink water and take a break, and during this break, the consequences of hydration showed itself. While a couple of the team were taking care of their business, there was suddenly a noise from their direction. The rest of the team, sans Don who was searching the perimeter and Ray who had gone to get the truck, perked up as a high pitched howl rung through the air. One cry was joined by another, and then another and suddenly it seemed like they were coming from everywhere. The separated team members came running back towards the recovery site and it seemed like the howling only got louder. Was it getting closer? Where was Don? Where was Socks? Out of the thicket came Socks, who we were all yelling for, while Don went into the thicket to see what was going on. It turned out to be a pack of coyotes who had been startled and because Socks went to investigate, began to howl and cry in warning. The high pitch screams were so startling and so unlike anything we had experienced that for a good 10 minutes, we just stood at the site and waited for Don to come out of the brush.

We finished our part in the recovery soon after Don had given us the all clear, and from there we made our way back to the trucks. Ray had returned to his truck to drive closer to us, as the walk back was a significant hike. Once we were back at our starting point, snacks and Mexican Cokes were shared and we toasted to a successful day.

We did not see the coyotes despite their close range, and the situation turned out the best it could have, but it makes one think about how the individuals who are making the journey North would have handled the same situation, not only at night, but with no protection or point of reference. We were also lucky enough to not have to walk back to our starting point, and especially after our first recovery, it emphasized how lucky we are to be in this position and how important the work that we assist with is. The terrain is so different at each ranch, but all of it is incredibly difficult to traverse. It is difficult in full body gear with access to water, snacks, and eyes on your back, so I could not even fathom the hardships and trauma that the migrants who walk these paths undergo.

Today was a success. The foggy weather in the morning did not define our day, and this is something that I will keep with me. Our days are subject to change and how it starts is not always how it will end. We might not have been able to give a positive ID at the moment, but we found somone who likely has family and friends that have been searching for them and a lot of things were learned. Each day will present successes whether or not a recovery is made and going into Day 3, remembering this will be especially important.