We slept in a bit later than yesterday, got ready, ate breakfast, and then loaded up in the car. Today, we planned to head to a new ranch where remains had previously been found. We began the day knowing it would be different than the previous two; we would be searching an area more diligently, staying eagle-eyed when looking for bones, fragments, or subtle clues. We prepared physically and mentally with extra water, a focused mindset, and confidence as we leaned into the uncertainties the day ahead might bring.

The drive to the ranch was long. It took nearly 45 minutes from entering the gate to reach the coordinates where the remains were located in the past. This travel time puts into perspective the sheer size of these ranches; some are a couple of hundred acres in size, others thousands, and some are even hundreds of thousands of acres. It emphasizes how easily something or someone could be missed entirely. After the long drive, we unloaded our gear, reviewed our search plan, and then lined up to begin searching through a massive motte.

This motte was unlike the others we have searched through. The underbrush was thick with grasses that had grown tall during last year’s unusually wet spring, and had died during the winter drought. The grasses were still rooted in the ground, but blown over and tangled together. However, to conduct the thorough search we aimed for, it was crucial to pull away the dense underbrush to reveal the sandy soil underneath to check for any signs of bones.

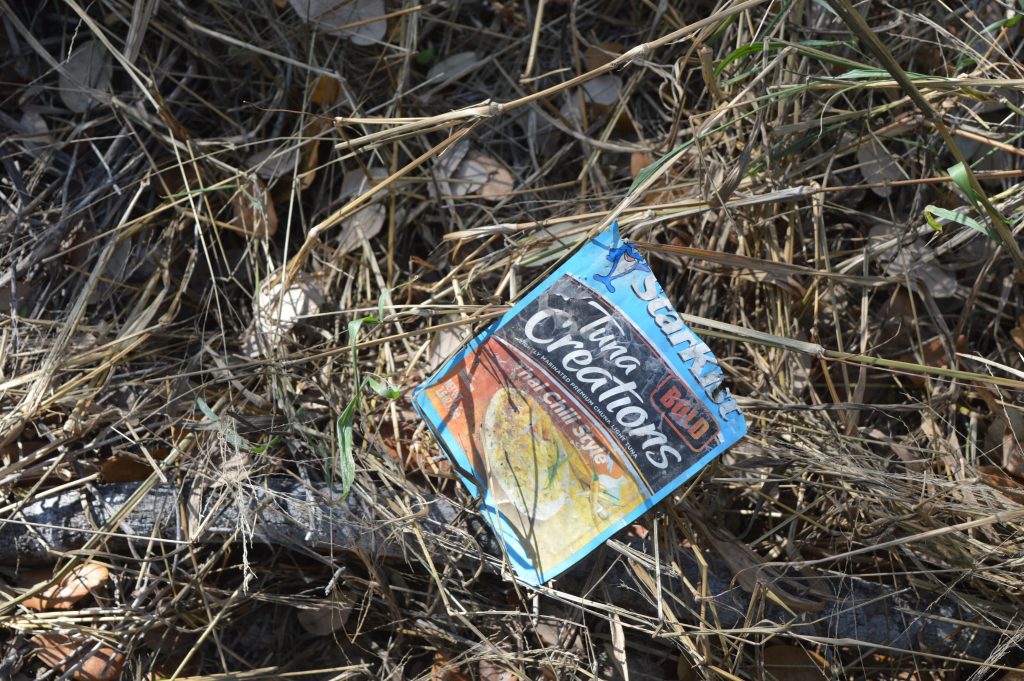

Another challenge we faced was the variation in taphonomy of the bones compared to what we have seen previously. Many of the animal bones have been sun-bleached, often presenting as bright-white, making them relatively easy to spot. However, if a bone is even partially buried (covered by blowing sand or pushed into the soft sand over time), it may be more brown in color and blend in with the soil. Searching through these mottes is especially crucial, as Don has taught us that migrants will often find a safe, shaded area to lie down and rest for a period of time. These areas often contain artifacts, which are items left behind during a migrant’s journey. Occasionally, an artifact will contain a “best by” or expiration date, which can provide context as to how long it has been there. Another technique I learned is that to tell the age of a plastic bottle, it can be stepped on. If the plastic crumbles or breaks apart, it is likely older; if it bounces back into shape, it is more recent.

We conducted line searches through thorny cacti, dense brush, and trees with branches poking in all directions. We were also spread farther apart, which made it hard to see everyone and make sure we were maintaining the same direction and pace. It was a true test of what we are learning in the Human Biology program at UIndy. Still, communication remained strong, and we searched carefully while only being poked by a few cacti. Sometimes, the mottes seemed to go on forever and only got thicker as we went in. My internal compass spun, and I was surprised by how easy it was to feel lost within the brush. However, it is just as easy to feel disoriented when viewing how vast the ranches are. Visibility stretches for miles, yet as you walk, it feels like you are making no progress at all.

The contrast made me reflect on the length and difficulty of the journey migrants endure to walk through these ranches; the dangers, the harsh environment, and the unknown about what lies ahead. Especially after seeing evidence of life within the dense brush, I can’t help but think about those who were here prior. The heaviness of not knowing what may be ahead is hard, but it empowers you to keep moving because finding any artifact or bones is important when recognizing who walked this path before us.

As we packed up for the day, it again took 45 minutes to exit the ranch. I sat in air-conditioning, looking forward to a warm meal, a shower, and a full night’s sleep. It had been a long, physically demanding day, but I had proper clothing, water, food, and a team beside me. I can’t fully imagine what it must feel like to walk these same areas while exhausted, exposed, and without those supports. Holding that reality with me, I leave today tired, humbled, and more aware of why this work matters. Tomorrow, we return to the brush with the same care, attention, and commitment to keep searching and showing up to land connected to many lives.